Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer in women after skin cancer. Although breast cancer also occurs in men, it is rare and accounts for less than 1 percent of all breast cancer cases.

-

Forms of breast cancer

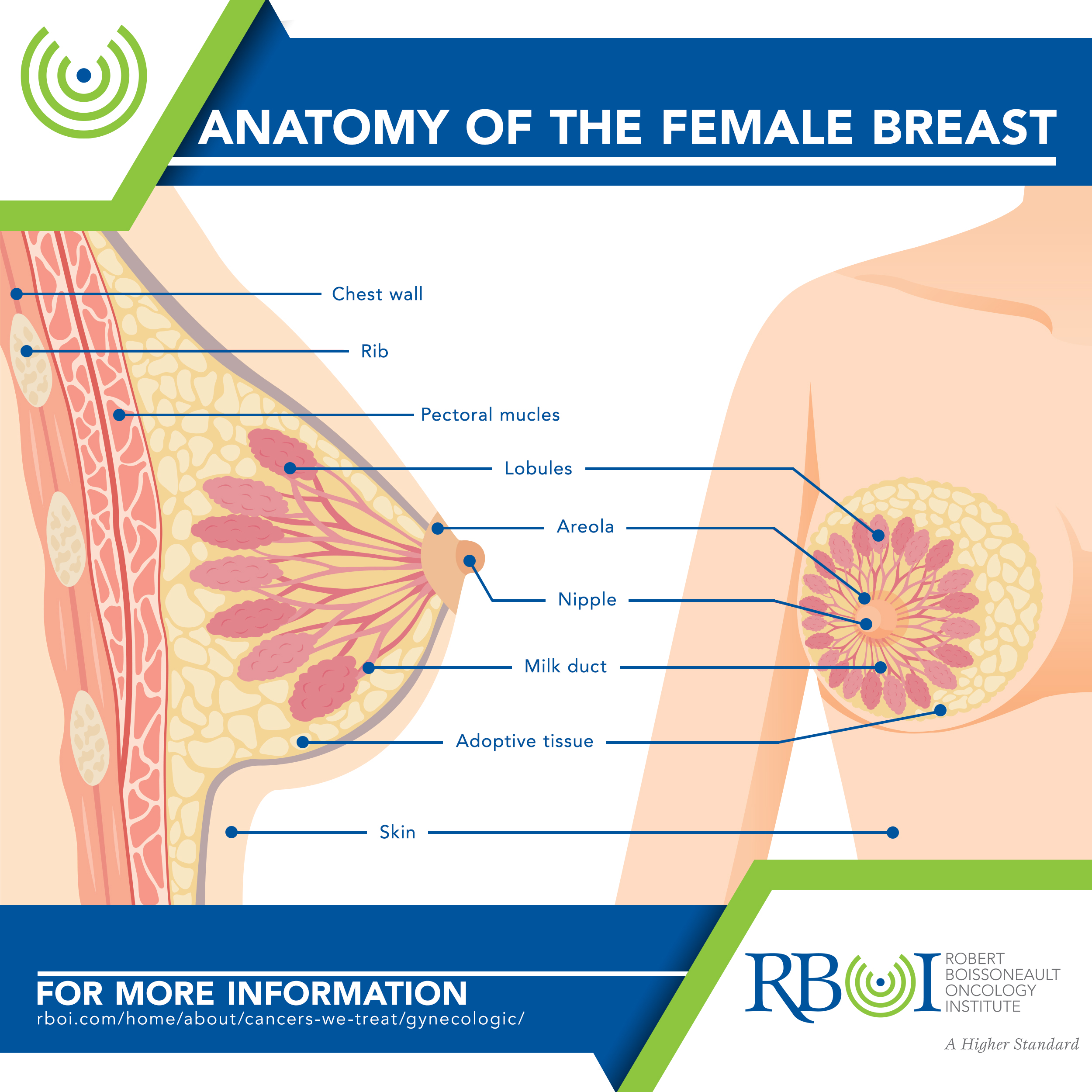

Ductal carcinoma starts in the cells lining the milk ducts. Most breast cancers are of this type. If it spreads outside the duct and into surrounding tissues, it is called invasive or infiltrating ductal carcinoma.

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is located only in the duct and begins as noninvasive. A high-grade DCIS may become invasive if left untreated.

Lobular carcinoma starts in the lobules of the breast. If it spreads outside the lobules and into surrounding tissues, it is called invasive lobular carcinoma.

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) is located only in the lobules and is not considered cancer. However, LCIS is a risk factor for developing invasive breast cancer in both breasts.

Inflammatory breast cancer accounts for about 1 to 5 percent of all breast cancers and is fast-growing.

Paget’s disease begins in the ducts of the nipple. Although it is usually in situ (noninvasive), it can also be an invasive cancer.

Additional, less common types of breast cancer include medullary, mucinous (or collod), tubular, metaplastic, and papillary.

-

Breast cancer has three main subtypes

Hormone receptor-positive — this breast cancer accounts for about 60 to 75 percent of cases. This subtype contains estrogen receptors (ER) and/or progesterone receptors (PR). This breast cancer can occur at any age, but is more common in post-menopausal women.

HER2-positive — this breast cancer accounts for about 15 to 20 percent of cases. This subtype contains a gene called human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), which makes the HER2 protein receptor. HER2-positive breast cancers grow more quickly and can be either hormone receptor-positive or hormone receptor-negative.

Triple-negative — this breast cancer accounts for about 15 percent of cases and does not contain ER, PR, or HER2 receptors. This subtype seems to be more common among younger women, particularly younger black women, and in women with a mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes.

-

Risk factors for breast cancer

Age, Alcohol, Breast density/breast implants, Certain benign breast conditions, DES exposure, Early menstruation and/or late menopause, Elevated estrogen levels in men, Family history, Gender, Hormonal forms of birth control, Hormone replacement therapy after menopause, Inherited risk/genetic predisposition, Personal history of breast cancer, Personal history of ovarian cancer, Physical activity, Race and ethnicity, Radiation exposure at a young age, Socioeconomic factors, Timing of pregnancy, Weight

Age — Breast cancer risk increases with age. Most cancers develop in women older than 50. The average age for men to be diagnosed with breast cancer is 65.

Alcohol — Compared with non-drinkers, women who have 1 alcoholic drink per day, including beer, wine, and spirits, have a very small increase in risk. Women who have 2 to 3 drinks per day have about a 20 percent higher risk of breast cancer compared to women who don’t drink alcohol, and they also have a higher risk of the cancer returning after treatment. The relationship of alcohol and breast cancer risk has not been studied in men.

Breast density/breast implants — Dense breast tissue may make it more difficult to find a tumor on standard imaging tests, such as mammography. Women with dense breasts have a breast cancer risk about 1.5 to 2 times higher than women with average breast density. Scar tissue from silicone breast implants also makes breast tissue harder to see on standard mammograms. X-ray pictures called implant displacement views allow a more thorough examination of breast tissue.

Certain benign breast conditions — Some non-cancer breast conditions are more closely linked to breast cancer risk than others. Conditions with higher risk include atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) and atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH). Women with these lesions have a breast cancer risk about 4 to 5 times higher than normal. Women with lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) have a much higher than normal risk of developing cancer in either breast.

DES exposure — Women given diethylstilbestrol (DES), a drug used from the 1940s through the early 1970s to try to prevent miscarriage, have a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer. Women whose mothers took DES during pregnancy may also have a slightly higher breast cancer risk.

Early menstruation and/or late menopause — Women who began menstruating before ages 11 or 12 or who went through menopause after age 55 have a somewhat higher risk of breast cancer, due to a longer lifetime exposure to estrogen and progesterone.

Elevated estrogen levels in men — Breast cancer risk in men may increase when their estrogen level is raised due to certain diseases, conditions, or treatments. These include (1) Klinefelter’s syndrome, which gives men higher levels of estrogen and lower levels of male hormones called androgens; (2) liver disease, such as cirrhosis, which can cause higher levels of estrogen and lower levels of androgens; and (3) low doses of estrogen-related drugs given for the treatment of prostate cancer.

Family history — Breast cancer risk increases if a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or child) was diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer, especially before age 50. If two first-degree relatives developed breast cancer, the risk can be five times higher than average. Risk also increases if many close relatives (grandparents, aunts and uncles, nieces and nephews, grandchildren, and/or cousins) were diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer, especially before age 50; if a family member developed breast cancer in both breasts; or if a male relative developed breast cancer. When looking at family history, your father’s side is just as important as your mother’s side in determining your personal risk for developing breast cancer. About 1 out of 5 men who develop breast cancer has a family history of the disease.

Gender — Breast cancer is about 100 times more common in women than in men.

Hormonal forms of birth control — Most studies have found that women using birth control pills have a slightly higher breast cancer risk than women who have never used them. This risk seems to return to normal over time once the pills are stopped. Some studies have found increased risk in women receiving Depo-Provera birth-control shots, but that risk is not found in women 5 years after the shots are stopped. Some studies have shown a link between the use of hormone-releasing IUDs and breast cancer risk. Few studies have looked at the relationship between breast cancer risk and the use of birth control implants, patches, and rings.

Hormone replacement therapy after menopause — Using hormone therapy with both estrogen and progestin after menopause increases a woman’s risk of breast cancer. Women who have taken only estrogen for up to 5 years, without previously receiving progestin, appear to have a slightly lower risk of breast cancer, but some studies have found increased risk of ovarian and breast cancer in women who took estrogen for more than 15 years. A woman’s breast cancer risk seems to return to that of the general population within 5 years of stopping treatment.

Inherited risk/genetic predisposition — Mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes are linked to an increased risk of breast, ovarian, and other cancers. A man’s risk of breast cancer, as well as the risk for prostate cancer, is also increased if he has mutations in these genes. Other mutations or hereditary conditions that present an increased breast cancer risk include Lynch syndrome (linked with the MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 genes); Cowden syndrome (CS, linked with the PTEN gene); Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS, linked with the TP53 gene); Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS, linked with the STK11 gene); ataxia telangiectasia (A-T, linked with the ATM gene); hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (linked with the CDH1 gene); and mutations in the PALB2 or CHEK2 genes. However, these mutations are far less common than those in BRCA1 or BRCA2 and do not increase the risk of breast cancer as much.

Personal history of breast cancer — A woman who has had breast cancer in one breast has an increased risk of developing a new cancer in either breast. Although this risk is low overall, it is higher for younger women with breast cancer.

Personal history of ovarian cancer — Women diagnosed with hereditary ovarian cancer caused by a BRCA gene mutation have an increased risk of breast cancer.

Physical activity — Decreased physical activity is associated with an increased risk of developing breast cancer, and with a higher risk of cancer returning after treatment. Regular physical activity may protect against breast cancer by helping women maintain a healthy body weight, lowering hormone levels, or causing changes in a woman’s metabolism or immune factors. Increased physical activity is associated with a decreased breast cancer risk in both women and men.

Race and ethnicity— White women are more likely to develop breast cancer than black women. However, among women younger than 45, black women are more likely than white women to develop breast cancer and to die from the disease. Survival differences may be related to differences in biology, other health conditions, and socioeconomic factors affecting access to medical care. People of Ashkenazi or Eastern European Jewish heritage may be more likely to have inherited a BRCA gene mutation, which would increase their breast cancer risk. Breast cancer is diagnosed less often in Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Native American/Alaska Native women. Both black and Hispanic women are more likely to be diagnosed with larger tumors and later-stage cancer than white women, but Hispanic women generally have better survival rates than white women. Breast cancer diagnoses have been increasing in second generation Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic women, likely related to changes in diet and lifestyle associated with living in the US.

Radiation exposure at a young age — Women who were treated with radiation therapy to the chest for another cancer (such as Hodgkin disease or non-Hodgkin lymphoma) when they were younger have a significantly higher breast cancer risk. Radiation treatment after age 40 does not seem to increase risk, and no risk has been found from the very small amount of radiation a woman receives during a yearly mammogram.

Socioeconomic factors — More affluent women in all racial and ethnic groups have a higher risk of developing breast cancer than less affluent women in the same groups. However, women living in poverty are more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage and are less likely to survive the disease than more affluent women.

Timing of pregnancy — Women who had their first pregnancy after age 35 or who have never had a full-term pregnancy have a higher risk of breast cancer. However, pregnancy seems to increase the risk of triple-negative breast cancer.

Weight — Recent studies have shown that postmenopausal women who are overweight or obese have an increased breast cancer risk. These women also have a higher risk of cancer returning after treatment. Women who are overweight also tend to have higher blood insulin levels, which have been linked to breast cancer. Some research suggests that being overweight before menopause might increase the risk of triple-negative breast cancer. Being overweight or obese also increases breast cancer risk in men.

-

Symptoms of breast cancer

A lump that feels like a hard knot or a thickening in the breast or under the arm. It is important to feel the same area in the other breast to make sure the change is not a part of healthy breast tissue in that area.

Change in breast size or shape

Nipple discharge that is sudden, bloody, or occurs in only 1 breast.

Physical changes, such as a nipple turned inward or a sore in that area

Skin irritation or changes, such as puckering, dimpling, scaliness, or new creases.

Warm, red, swollen breasts with or without a rash, with dimpling, resembling the skin of an orange, called “peau d’orange”.

Breast pain, especially if it does not go away. Pain is not usually a symptom of breast cancer, but it should be reported to a doctor.Women usually do not have any signs or symptoms when diagnosed with breast cancer. Mammograms can detect breast cancer early, possibly before it has spread.

-

Symptoms of metastatic breast cancer to all sites

Loss of appetite

Unexplained weight loss

Nausea

Vomiting

Fatigue -

Metastatic breast cancer can also cause symptoms to the following sites

Bone

- Bone, back, neck, or joint pain

- Bone fractures

- Swelling

Brain

- Headache

- Nausea

- Seizures

- Dizziness

- Confusion

- Vision changes, such as double vision or loss of vision

- Personality changes

- Loss of balance

Liver

- Yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes, called “jaundice”

- Itchy skin or rash

- Pain or swelling in the belly

- Loss of appetite

Lung

- Shortness of breath

- Difficulty breathing

- Constant dry cough

-

How is breast cancer treated with radiation?

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT), delivered from outside the body, is the type of radiation therapy used most often to treat breast cancer. Methods of EBRT include intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), 3D-conformal radiotherapy, and hypofractionated radiation therapy.

Brachytherapy, or internal radiation, involves the placement of a radioactive source inside the body. This treatment is not widely used for breast cancer, but might be an option to treat a small tumor that has not spread to the lymph nodes.

Intra-operative radiation therapy is given using a probe in the operating room. This treatment is not widely used for breast cancer, but might be an option to treat a small tumor that has not spread to the lymph nodes.

Not all women with breast cancer need radiation therapy, but it may be used in the following cases

After breast-conserving surgery (BCS, also called a lumpectomy), to help lower the chance that cancer will return in the breast or in nearby lymph nodes. Radiation is usually delivered first to the entire breast, followed by an extra boost of radiation to the tumor bed, where the cancer had been removed.

After a mastectomy, especially if the cancer was larger than 5 cm (about 2 inches), or if cancer is found in the lymph nodes. Radiation is focused on the chest wall, the mastectomy scar, and the places where any drains exited the body after surgery.

If cancer was found in the lymph nodes under the arm (axillary lymph nodes), radiation might be focused on that area. Other areas receiving treatment might include the nodes above the collarbone (supraclavicular lymph nodes) and the nodes beneath the breast bone in the center of the chest (internal mammary lymph nodes).

Before surgery, to shrink a large tumor and make it easier to remove. This approach is considered only when a tumor cannot be removed with surgery.

If cancer has spread to other parts of the body, such as the bones or brain.

Click here to learn more about RBOI’s radiation treatment options

Click here to watch a walk-through of what is involved in radiation treatment at RBOI

More extensive information about breast and other cancers may be found at these sites:

American Cancer Society: Cancer.org

American Society of Clinical Oncology: Cancer.net

National Cancer Institute: Cancer.gov